If you’ve ever lined up three quotes for what looks like the same projector headlight and wondered why the numbers are far apart, you’re not missing a secret spec sheet. You’re seeing different assumptions inside the pricing.

This note is from the factory side for B2B buyers. It’s not about “which tier to choose,” how to audit suppliers, how to install, or how to handle compliance. It’s simply: what we are pricing, what changes the quote, and what information makes your next reorder price stable instead of surprising.

1) What a unit price really contains (the parts nobody lists)

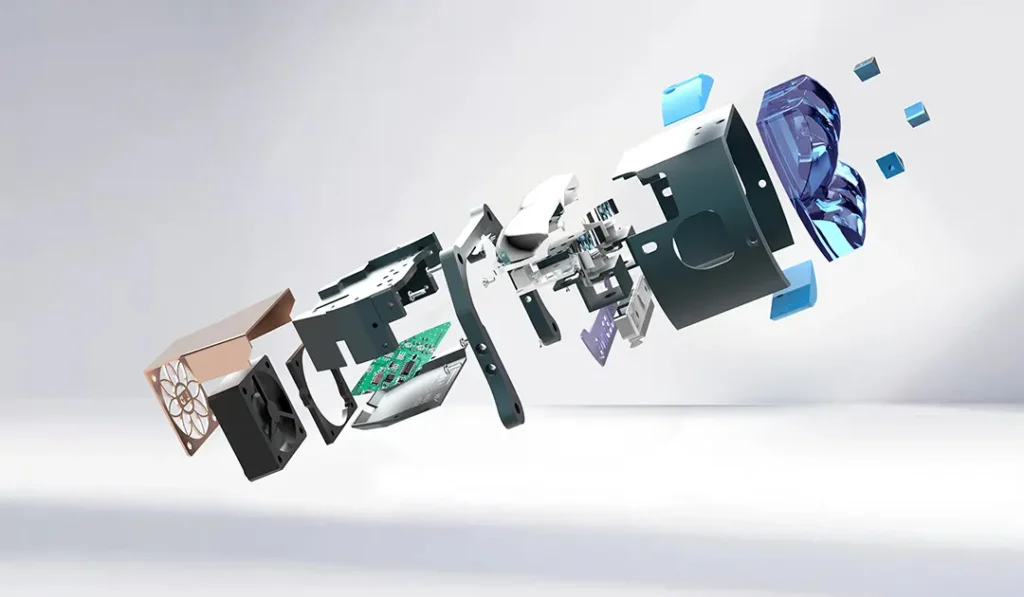

A projector headlight quote isn’t just “materials + labor.” Internally, we’re pricing six buckets:

- BOM (bill of materials)

Optical parts, housing materials, electronics, wiring, seals, fasteners, accessories. - Direct labor (minutes per unit)

Assembly time, handling time, rework time, packing time. - Yield (scrap + rework expectation)

How many units we expect to reject, rework, or scrap to meet your acceptance criteria. - Test time (and test labor)

Not “tested or not,” but how many checks, at what sampling rate, with what pass/fail rules. - Packaging (materials + packing labor + cube)

Carton/inner protection cost and the dimensional size that drives shipping cost. - Commercial risk

Payment terms, currency exposure, raw material volatility, and warranty exposure.

Most pricing gaps come from #2 (time), #3 (yield), and #5 (packaging cube), not from a single “better part.”

2) The 8 “price switches” you control (even if you don’t realize it)

These are the inputs that move quotes in real programs. When they’re undefined, different suppliers assume different defaults—so comparisons get messy.

2.1 Cycle time (minutes per unit)

Small process expectations change labor fast:

- extra alignment verification steps

- tighter cosmetic handling rules

- more careful accessory kitting

Even if the BOM looks similar, a longer build has to cost more.

2.2 Acceptance rules (what you consider sellable)

You don’t need an engineering spec. You do need clarity like:

- “Minor marks inside housing are acceptable; lens marks are not.”

- “Tab cosmetic scuffs are acceptable; broken tab is not.”

The stricter the acceptance, the more time we spend preventing, catching, or reworking defects.

2.3 Scrap vs rework policy

A low quote often assumes aggressive rework (or very generous acceptance).

A conservative quote assumes higher scrap to avoid shipping “borderline” units. That raises unit cost, but reduces downstream friction.

2.4 Inspection intensity (how often, not just “yes”)

“QC included” means nothing unless you define:

- sampling rate (e.g., per lot / per shift / per shipment)

- what’s checked (appearance, function, key dimensions, etc.)

- what is recorded (or not)

More inspection is more labor and more captured rejects—both affect price.

2.5 Packaging cube (dimensional weight)

Headlights are a classic “shipping air” product. Two packaging designs can:

- protect the product equally well

- cost similar in cardboard

- but differ a lot in outer dimensions

That changes freight. So the real comparison is often landed cost, not EXW/FOB unit price.

2.6 Kitting complexity (what’s in the box, and how it’s packed)

If you want:

- separate accessory bags

- multiple language manuals

- barcode labels on inner/outer

- extra protective films

…that is real labor and real error risk, so it gets priced.

2.7 Order rhythm (forecast stability)

Stable monthly reorders let us:

- buy materials in better batches

- plan labor

- avoid rush costs

One-off orders and unpredictable changes force us to price “just in case.”

2.8 Payment terms & price validity

Longer payment terms, longer price validity, or volatile materials increase risk.

Some suppliers price that risk up front; others don’t—and then renegotiate later.

3) Three “cheap quote” patterns that usually become expensive later

This isn’t about bad actors. It’s about quotes built on optimistic assumptions.

3.1 The quote assumes perfect yield

If acceptance expectations are high but yield is priced like it’s perfect, something will give later:

- drifting workmanship

- looser internal acceptance

- sudden “material alternatives”

- slow argument cycles when issues appear

3.2 The quote assumes minimal packaging cost and minimal freight impact

You can save on packaging materials and still lose money on freight or damage claims if cube isn’t controlled and protection isn’t matched to your distribution reality.

3.3 The quote assumes “simple kitting,” but your channel isn’t simple

If your downstream reships single units, splits cartons, or needs barcode discipline, the “standard pack” becomes a hidden cost center.

4) How to compare quotes without guessing (a simple normalization sheet)

When you ask multiple suppliers for pricing, don’t compare feature claims. Compare assumptions.

Use this normalization list in your RFQ

- Program type (one line): aftermarket / OEM-like / custom (just for expectation setting)

- Sellable standard: what cosmetic/fit issues are unacceptable in your channel

- Build expectation: any must-have kitting/labeling/pack-out rules

- Inspection expectation: sampling level + which checks matter most

- Packaging target: single-unit vs master carton reality + any cube limits if you have them

- Order plan: first order + expected reorder rhythm

- Commercial terms: payment, currency, price validity period

If two suppliers price the same inputs here and still differ wildly, then you have a meaningful discussion.

5) What reduces your price (without reducing your program quality)

These are the “boring” buyer behaviors that let a factory quote tighter:

5.1 Freeze the configuration before mass production

Not a long contract—just fewer midstream changes. Stability lowers waste.

5.2 Standardize packaging early

If we lock a pack-out and carton size, we can optimize material purchasing and reduce packing variation.

5.3 Give a real reorder rhythm

Even a simple forecast band (e.g., “500–800 sets/month”) improves pricing more than most buyers expect.

5.4 Keep kitting disciplined

Every extra bag, label, insert, or variation seems small until it becomes the main source of packing errors. Fewer moving parts = lower cost.

6) The takeaway: the “best price” is the one you can reorder

A projector headlight quote is a prediction of time, yield, and risk—not just a parts list.

If you want pricing that stays stable, don’t fight for a lower number by leaving things vague. Write down the assumptions that matter—acceptance, inspection, packaging cube, kitting rules, and reorder rhythm. That turns pricing into something you can manage, explain internally, and scale without drama.